David Worsfold

Be prepared for everything and be prepared for nothing. That seems to be the confusing message from central banks when it comes to interest rates and quantitative easing.

The first round of autumn policy meetings, in particular at the Fed and the Bank of England, produced inaction and a barrage of contradictory messages in their wake. Since then, it has become increasingly clear that different central banks are on very different trajectories. The Fed is likely to raise rates in December, while the ECB is more committed than ever to monetary easing.

Policymakers are feeling increasingly boxed in. They are looking over their shoulders at a wide range of threats to the gradual, but still vulnerable, economic recovery. China, Greece, Japan, collapsing commodity prices, banks still sitting on huge levels of corporate bad debt all have the potential - especially in combination - to slow down growth.

How can policymakers respond to that?

QE is already at the limits of sustainability and interest rates are on the floor.

Negative interest rates? Unthinkable once but now a reality, at least as a short-term strategy to discourage banks from sitting on piles of cash.

Janet Yellen touched on the fears of central banks in a major speech on 24 September when she warned of the consequences of a sudden jump in rates further damaging any fragile recovery. But without higher rates, the Fed and its fellow central bankers are going to have nowhere to go if – or rather when – recession returns in the next few years. They want elbow room. Get rates up now so they can pull them back when they need to.

Leave it too long however, and interest rates could jump suddenly. That would be painful for many insurers, especially those underwriting long term guarantees to policyholders, still a common feature in Germany and other central European markets. They will have to be prepared for a short term shock if this happens, as it has the potential to wipe out the unrealised gains they have been sitting on and which have kept them solvent. On the flip side, while they are readjusting their portfolios, it could also open up market opportunities for new insurers who wouldn’t have to reposition investment portfolios and could take advantage of higher rates straightaway.

In contrast, a gradual but sustained upward movement of interest rates should be good news for most insurers as it will enable them to reinvest at the new rates, making it easier to match guarantees.

Even the status quo holds dangers as using unrealised gains can only work for so long, before companies have to seek value and higher returns elsewhere, if they are not to find themselves exposed to creeping insolvency. Those who have been hedging an interest rate rise could face issues in terms of finding collateral if the rises are delayed because of sustained low inflation in the main economies, exerting pressure on liquidity. For the UK, it is an increasingly more likely scenario if the response to two months of deflation is any guide.

Despite the inflation figures, most insurers are still hoping for a gradual rise in rates kicking off before the end of this year. All eyes will be on the December Federal Open Market Committee, although expectations that it will trigger any global bout of tightening are low, to say the least.

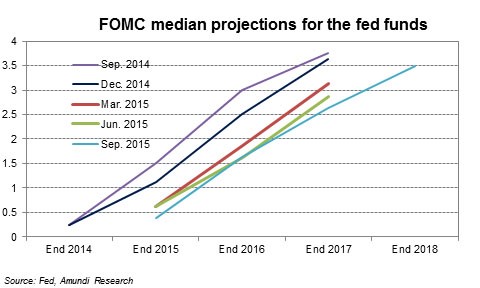

The fear of being boxed in will have to be put alongside the dangers of inhibiting recovery so even in the US, the rises will be cautious. Analysis of the FOMC projections illustrates well the growing caution of its members (see graph).

This is likely to be reflected in the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee where the gap between the hawks such as Ian McCafferty and the doves led by Ben Broadbent and the Bank’s own chief economist Andy Haldane seems as wide as ever. There will be a middle way and it will probably follow very closely the Fed’s moves.

Alongside the key question of when – not if – rates will start to rise is the question of where will it end? Not at 5.25%, the peak during the previous economic cycle: there seems little disagreement on that.

The current Fed projections take us to 3.5% by the end of 2018 but that seems too long, and too far. Many commentators are now focusing on a peak of between 2.5% and 3% being reached sometime in 2017. That would satisfy most insurers, giving them a chance to gradually re-shape portfolios, making them feel more robust and capable of withstanding other economic shocks. But it will still put a premium on creatively managing portfolios, seeking out value wherever it can be found.