David Worsfold

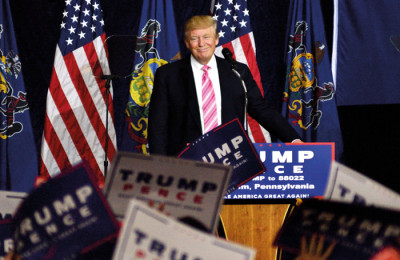

Markets, commentators and investors have been turning somersaults trying to come to terms with the implications of the Trump Presidency. They had better get used to doing so as the new President is busy tearing up the rulebooks, especially the one entitled global trade.

In the run-up to the election in November, few commentators and investment managers really took the possibility of Donald Trump sitting in the Oval Office seriously. It was rather like the run-up to the Brexit vote in the UK. Almost every financial institution claimed to have a contingency plan in case the Leave vote came out on top but, in truth, few of those plans ever got further than the back of a single envelope.

Little serious analysis was done of Trump’s economic and fiscal policies and even those who did bother to study them usually came to the conclusion that he could never carry his often brutal campaign rhetoric through to office should he win.

He did win but the initial shock quickly eased into the background in financial markets. Wall Street recovered its poise and pushed the Dow Jones Index on through the 20,000 barrier.

Yes, there were bumps in some sectors. Big Pharma, for instance, having feared tough action to curb pricing under a Clinton Presidency, bounced on Trump’s election, only to fall back when it became clear – well, as clear as anything does with President Trump – that he too isn’t keen on Big Pharma either.

But it is his attitude to international trade that is becoming one of the key features of the first phase of his Presidency. Economists, analysts and politicians around the world have been stunned by the ferocity of his attacks on global trade agreements forged through many long, hard years of negotiation.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. He said that is what he would do and he is now in a position to deliver those promises. Thoughts that it might take time to swing Congress behind this radical path proved little comfort when Trump tore up a series of multi-lateral trade agreements as world leaders quietly fumed at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

The US President has wide executive powers when it come to trade agreements. The Trade Act of 1974 gives the President the authority to withdraw from trade agreements and to impose import tariffs of up to 15% for up to 150 days without consulting Congress. We have seen the agreements being ditched, so the next question has to be when will we start seeing the tariffs and where will they fall?

This is where all investors, especially large institutional investors, are going to have to be smart, aware and fleet-footed. There will be some big losers, and also some big winners.

China is worried. One of the first world leaders to take to the stage in Davos and attack the new US president’s protectionist stance was the Chinese President Xi Jinping. Why? Because since it joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, China has been a big beneficiary from the shifts in global trade, especially during the pre-crisis expansion. Trump doesn’t like China and China knows that, so don’t expect the White House to worry about the negative impact most economists are predicting for China.

Latin America could be hit hard too as plenty of American manufacturing has moved south in recent decades and Trump has made it clear he wants that reversed.

The unions are loving it and the big manufacturers, especially in the automobile sector, have started making supportive noises.

Who will win if these policies are effective?

It is unlikely to be the people who voted for Trump, although there could be some interesting shifts in employment patterns if Trump manages to restrict employment of foreign labour inside the US. This is likely to vary significantly state-by-state.

If some of the major manufacturers do repatriate whole factories and processes to the States, there will be an uplift in the construction sector, further boosted if Trump gets round to delivering his promises on infrastructure investment.

New factories won’t employ 1000s of new workers, however. They will employ thousands of brand new robots. A study from the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University published last year found that only 13% of US blue collar jobs lost over the last decade had gone because of global trade deals. The rest had been lost to automation.

Whether the work stays in China or Latin America or returns to the US, the robotics and capital goods sectors will be the big beneficiaries.

If all of this sounds unsettling and the generator of the very volatility and uncertainty that financial institutions most fear in the post-Solvency II world, then look forward a few months at the potential for conflict between the White House and the Federal Reserve.

President Trump has made little secret of his dislike of Janet Yellen, Chair of the Fed. With the Dollar already wobbling and inflation growing as a threat, she might feel it prudent in context of conventional monetary policy to raise interest rates quite quickly. If this stalls economic growth or consumer spending – or at least is seen to in the eyes of the administration in the White House – we could be in for very bumpy ride.

Trump may have torn up some of the old rule books: the trouble is no-one has anything substantive to put in their place. The financial markets are playing by new rules but they don’t actually know what those rules are.