David Worsfold

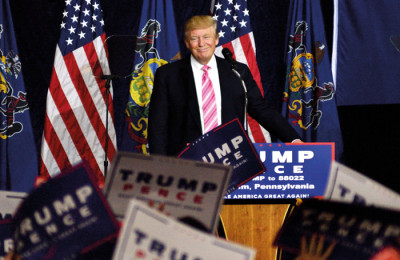

Populism? That was very 2016 wasn’t it? The vote for Brexit and the election of Donald Trump had many warning that 2017 could be even worse. Largely, we have avoided the worst. We don’t have far-right leaders in power in Holland and France, and Angela Merkel should survive the forthcoming German election. The relief felt at the results of the elections in Holland and France needs to be severely tempered, however, as the waves of populism continue to wash over us.

The Dutch still do not have an effective government and are now talking about October being the earliest one might be in place. Nearly six months have passed since the Dutch general election on March 15 and endless rounds of negotiations since then have failed to produce any prospect of a stable government. The problem is that the four main centre and centre-right parties are trying to cook up a deal to exclude the far-right Freedom Party (PVV) from government despite them holding the second highest number of seats after Prime Minister Mark Rutte's People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD).

The Dutch are used to extended periods without a government after inconclusive elections. On 1 September, 170 days passed without a government. It took Rutte a relatively quick 54 days in 2012 to form a ruling coalition. The record still stands from 1977 when it took 208 days.

The absence of a strong Dutch voice in the European Union as the Brexit negotiations gather pace is probably detrimental to the chances of a rational approach to the future trade in financial services. Not only does the Dutch financial services sector have many similarities with the UK’s – with a strong independent intermediary sector for instance – they are also not in the increasingly robust battle to attract UK firms having to re-domicile in then EU, so have no axe to grind.

The election of Emmanuel Macron as French president prompted an even louder sigh of relief among those who feared the rise of Marine Le Pen could have seen a right-wing populist to match the destructive fervor of Donald Trump installed in the Élysée Palace. What many have failed to appreciate is that Macron himself is a creature of populism. His new En Marche! Party not only swept him to power but propelled a legion of political novices into the French Parliament as the old parties were brutally rejected.

Macron’s ambitious agenda for modernising France played well in the financial capitals of the world, long concerned that the country’s restrictive labour laws and generous pension provision in particular would drag it down just as the rest of Europe was limbering up for its hoped-for post-Brexit economic boom.

Don’t hold your breath.

His popularity ratings are spiralling downwards and he is already getting cold feet over some planned reforms, such as the switch to a PAYE income tax system which has been postponed. That is before the unions and his left-wing opponents take to the streets over his plans to radically overhaul the very restrictive labour laws in France. They are planning a national day of strikes and demonstrations on 12 September and the world will watch nervously to see how well supported they are.

If the French government is reduced to the status of a lame duck within the EU this would leave the Brexit agenda being set almost exclusively by Germany. This might turn out to the UK’s advantage as German business groups are already agitating for talks to start on what the post-Brexit trade deal – transitional or otherwise – might be. This is closer to the current UK government’s negotiating position than to the official EU position and a sharper focus on trade would definitely be welcomed in City boardrooms.

Across the Atlantic, two big issues affecting corporate America and the financial sector will loom large on the agenda – tax reform and regulation.

President Trump is talking about trying to force through as much of his ambitious tax reform agenda as possible this autumn, many elements of which will find enthusiastic supports among Republicans in Congress. If some of the changes to corporate taxation make it through, it will change the post-tax balance sheet of many US companies, forcing a major re-assessment of US equity holdings. Analysts are already suggesting that the sustained Wall Street bull market could be given a further boost, although warning that there are many potential hurdles to be overcome before the reforms become a reality.

Another area Trump is taking aim at is financial regulation. He has already issued one executive order pointing firmly in the direction of relaxing many of the post-financial crisis regulations. This has set the President on the road to conflict with the chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, who has made it clear that the regulations must stay, although accepting the case for some reform.

She recently acknowledged that the Volcker rule, which limits proprietary trading by banks, is too complicated but opposes scrapping it because it there is, she argues, a need to curb risky trading financed with taxpayer-guaranteed deposits. She similarly accepts the regulations covering small and medium-sized banks are more burdensome than they need to be and that elements of the Dodd-Frank Act could be improved.

Her opposition to any significant repeal or watering down of the regulations, especially around capital adequacy, is playing out well in Europe where regulators are worried at the prospect of America pulling away from the post-crisis consensus.

These issues form the backdrop to the Insurance Investment Exchange’s first autumn event, a half-day morning seminar in London on 19 September. Entitled ‘New Assets, Old Liabilities: Enhancing Returns on Capital’, it will take an in-depth look at how insurance portfolios and capital management are evolving in response to these strains and where the best opportunities for improving returns on hard-pressed investment portfolios are to be found. Insurers and other industry participants may register here.