David Worsfold

Illiquid assets have been gaining in popularity among insurers over the last couple of years. This has been a steady trend, not a headlong rush, but it is sufficient to start gently ringing the alarm bells at the Bank of England and the Prudential Regulation Authority.

The growing interest in illiquid assets has been reflected in the audience polling among participants at the Insurance Investment Exchange’s quarterly seminars.

The Bank’s concerns were set out at the end of last month by David Rule, the executive director of insurance supervision, in a little-reported speech at a Westminster and City conference entitled Bulk Annuities – The Expanding Market.

A lot of Rule’s focus was on the expansion of the equity release market and the potential impact of a slump in house prices could have on margins and profitability, but he also aired some serious concerns about the use of equity release as an asset.

He made it clear that the PRA recognises the potential value of equity release to consumers, especially as £1.8 trillion of the £2.6 trillion of homeowner equity in England belongs to people over 55. However, he urged insurers to look carefully at the business model and how it might cope if the housing market does not perform as positively as anticipated.

“First, simple projections suggest that equity release mortgage books could face difficulties in scenarios of flat, as well as falling, nominal house prices. Second, UK experience is that although house prices do diverge across regions, they tend to move in the same direction. So insurers might not be able to diversify away the risk to any significant extent. Third, the experiences of, for example, the Japanese property market between 1990 and 2010 and the Italian property market between 2007 and 2017 show that it is possible for house prices in an advanced economy to fall over a period of decades.”

He said the no-negative-equity guarantee that is now a common feature of equity release plans held particular dangers if house prices stagnated. The roll-up of interest on loans could mean that this becomes a liability for the lender, or at least an asset of diminishing value.

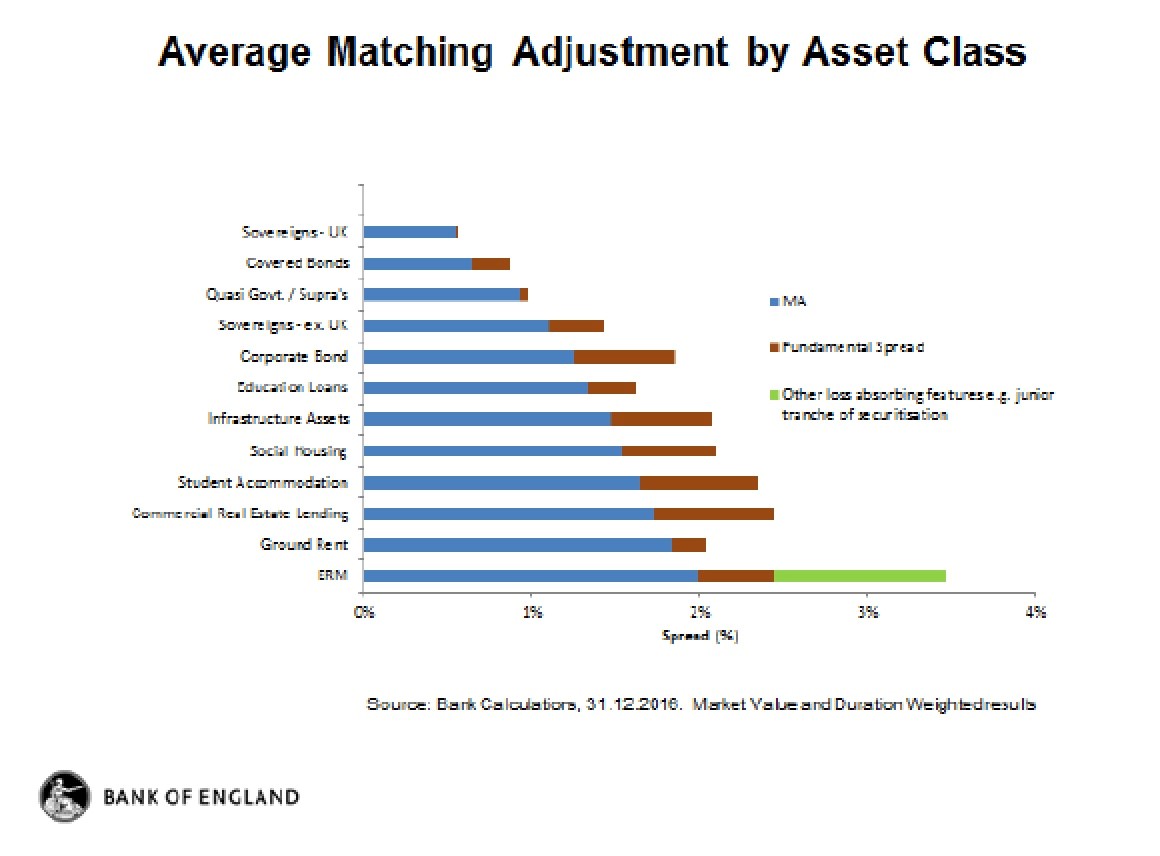

This leads directly to the PRA’s concerns about how equity release appears on the asset side of the balance sheet and how it – along with other illiquid assets – is treated under Solvency II and the Matching Adjustment regime. One of the arguments deployed by the pan-European regulator EIOPA (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Regulatory Authority) in rebuffing the pressure from insurers for a more generous treatment of illiquid assets under Solvency II has been its fear of what might happen when portfolios or particular assets come under stress and pro-cyclicality becomes a factor.

Rule took up this theme.

“But why is the Matching Adjustment on illiquid assets larger than on corporate bonds? One possibility is that that the wider spreads are compensating other investors for the risk that they might need to sell into secondary markets that are less liquid than the corporate bond market. The problem with this argument is that insurers are beginning to dominate a number of these markets, notably equity release mortgages.

“In at least some of these markets, it seems likely that they are now the marginal lenders and returns should therefore reflect the risks that they face”.

He said that the PRA saw particular dangers in the way insurers were treating equity release as an asset and getting it into their investment portfolios by the way of securitised notes.

“It should be no surprise that we are paying particular attention to the internal ratings of the securitised notes backed by equity release mortgages. These typically have a high matching adjustment, are complex and relatively large in value. They are subject to credit default and downgrade risks, like any other matching adjustment assets. But the drivers of default and downgrade risks are the risks on the underlying

mortgages, such as prepayment, longevity or the exposure to long-term house prices arising from the no-negative-equity guarantee.

“The essential point of SS 3/171 is that compensation for the risks taken by the insurer, particularly providing a no-negative equity guarantee, should not translate into a matching adjustment benefit on the restructured notes. Moreover, the compensation for risks retained by a firm as a result of the no negative equity guarantee must comprise more than the best estimate cost of the no negative equity guarantee.

“A best estimate cost of the no negative equity guarantee might be based on assumptions about likely long-term house price growth in excess of risk-free rates, extrapolating for example from historical experience. But long-term house price growth is a risk to which insurers are exposed”.

Although the main focus of Rule’s analysis was equity release, he did not separate it as an asset class from wider concerns about the growing prominence of illiquid assets in insurers’ investment portfolios. It might stand out in his analysis as the asset most likely to get those regulatory alarm bells ringing, but other property related assets are also being scrutinised by the PRA, given the growing reliance on the matching adjustment by some insurers.

1Solvency II: Matching Adjustment, unrated, illiquid assets and equity release mortgages. Prudential Regulation Authority SS 3/17.