David Worsfold

David Worsfold

“Equivalence”. The cheers echoed around the streets of the City of London, as newspapers carried a succession of optimistic reports from the Brexit frontline.

November brought promises of a breakthrough deal to enable UK financial services firms to keep trading in the European Union after Brexit, raising spirits and the pound sterling. Now that almost everyone accepts that passporting will be lost with no hope of a deal to preserve it, equivalence has been seen as by far the best option.

It was hardly surprising then that the reports, initially in The Times, that a deal had been done to ensure equivalence so long as UK and EU regulatory regimes remained aligned were greeted with a palpable sense of relief. It must have improved the mood at quite a few breakfast tables.

It turned out to be another false dawn, just like the Brexit Secretary Dominic Rabb’s promise that all the Brexit negotiations would be concluded by 21 November. Or Theresa May’s “95% done” comments earlier in October.

By lunchtime, the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, was on the social media airwaves giving everyone, so jubilant at breakfast, indigestion over their lunch.

“Misleading press articles today on #Brexit & financial services. Reminder: EU may grant and withdraw equivalence in some financial services autonomously. As with other 3rd countries, EU ready to have close regulatory dialogue with UK in full respect for autonomy of both parties”.

That’s it. No deal. Too much optimism and a reminder that the EU holds all of the cards.

This is how it is with Brexit. The politicians demonstrate daily that absolutely no-one has a clue where, when and how this will end.

They story changes daily. What was right today will be wrong tomorrow and right again the day after.

What the most prudent boardrooms in the City of London know, however, is that to plan for anything else than a hard Brexit would be foolhardy.

Many have already set up new subsidiaries. Lloyd’s of London has led the way with a major hub in Brussels, but across the London insurance market others have been plotting their own post-Brexit futures.

Firms have selected a variety of options, depending on the structure and parentage of their firms and the extent of the business they have across the European Union. No single model for post-Brexit operations has emerged and, at this late stage, it probably won’t.

Some major firms, of course, already have licenses in several European markets but this does not mean they are immune from having to take some major decisions about how to do business after Brexit – whether that be 29 March next year or at the end of a possible transition period.

For instance, it was a relieved AIG that announced on 26 October that it had received judicial approval to split its European subsidiary into two new entities. AIG International Group UK, or AIG UK, will be headquartered in London and AIG Europe SA, or AESA, will be domiciled in Luxembourg. AESA will have 21 branches across the European Economic Area and Switzerland, and both new companies will begin writing business on 1 December 2018. This new structure will replace AIG’s integrated European operation, which is currently managed from its London offices in Fenchurch Street.

The choice of Luxembourg is one that has been popular with many firms as the International Underwriting Association of London revealed last month when it delivered its annual report on the market.

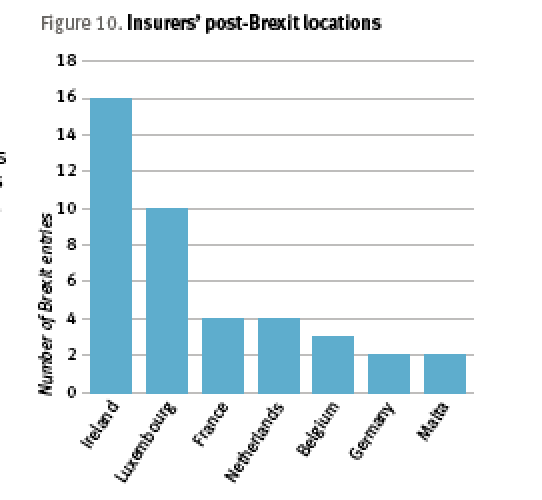

It found that Ireland was the most favoured location because many firms already had operations based there. Among those needing to set up something from scratch Luxembourg has been the top choice. Hiscox is among the major insurers to re-domicile parts of its business vulnerable to a chaotic Brexit to the Grand Duchy. France, despite a vigorous charm offensive among UK financial institutions, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and Malta have so far only attracted a few firms.

What many have found is that the regulators are sticking to the tough line set out this time last year by the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) when it said it would not tolerate “letter boxes or empty shells”.

If firms are managing capital, investments, underwriting and claims in their new locations, the national regulators have been told to insist that the senior management decision-making has to reside in those locations too. Anecdotal evidence among some of the insurers re-domiciling is that this is proving tougher than they expected. Not only are they having to move more senior people than they anticipated but they are also finding it hard to recruit when they require experienced local practitioners.

Beware those Brexit false dawns. They will become more frequent as the 29 March B-Day looms larger on the horizon.