The below piece on deglobalisation first appeared in the Guardian on 2nd December 2016. Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

The below piece on deglobalisation first appeared in the Guardian on 2nd December 2016. Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

But this narrative has become worn and no longer fits the facts. In recent months, there has been a backlash, accompanied by emotive talk about the reversal of globalisation and the battle for society’s future. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development used its latest health check on the global economy to warn of the costs of protectionism.

The hand-wringing is half a decade too late, because globalisation is already dead and we are already some miles into the journey back.

Donald Trump and Theresa May are not flagbearers in the distance, they are catapults battering at the walls. Trump’s stated intent to pull the US out of the TPP on his first day in office underlines the new reality we inhabit, as does the European Union’s recent troubles closing a trade agreement with Canada thanks to Wallonia’s obstinance.

Today, we have a new meme – deglobalisation – as people turn their backs on an interconnected world economy and societies turn iconoclastic.

It is not for the first time.

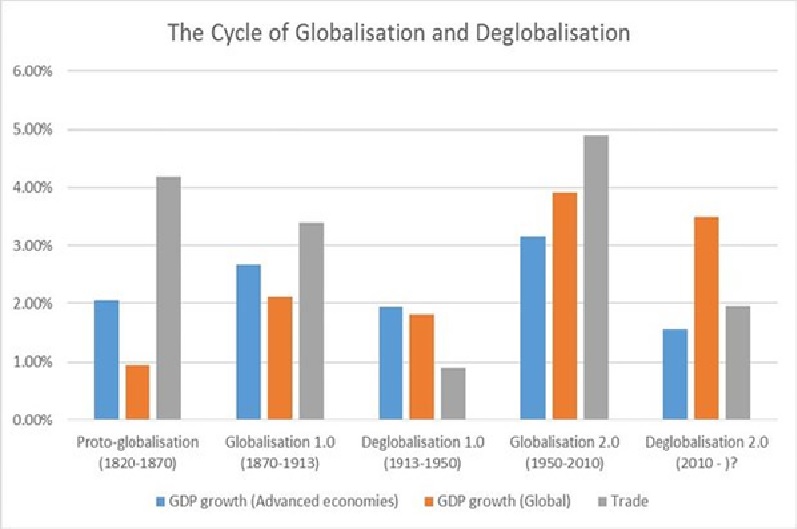

Globalisation may be defined as when trade across nations is growing faster than GDP. People interact more, transact more and create more wealth. Deglobalisation is the alternate state where trade grows less than GDP. Countries focus inwards, trade declines as a proportion of GDP and growth shrinks. A clear cycle of the two emerges over history.

Phases of globalisation and deglobalisation over the last two centuries. Illustration: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

- Proto-globalisation (1820-1870): Rapid global trade growth, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the spread of European colonial rule

- Globalisation 1.0 (1870-1913): Empire building became the norm. Rapid advancements in transport and communications grew trade. But rapid change also meant volatile bouts of economic obsolescence and crisis

- Deglobalisation 1.0 (1913-1950): Limited growth, unequal outcomes and a huge debt overhang from previous decades stoked economic nationalism and protectionism. Trade fell and a collective failure to tackle deeper structural issues led to the 1930s

- Globalisation 2.0 (1950-2010): Since then, we have been on a tearaway expansion with unparalleled growth of both global trade and GDP

- Deglobalisation 2.0 (2010-?): The last financial crisis focused policymaker attention inwards and crystallised the growing sense of social disenfranchisement. A toxic mix of suppressed wages, rocketing debt and political myopia have largely destroyed the allure of globalisation.

This is more than a sense of ennui. Global trade today is not slowing down but has plateaued – hardly a barometer of rude global health. After their peak in January 2015, global exports fell -1.6% by the end of August 2016. The blame lies not with commodity price falls, but shifts in trade policy. Protectionism is en vogue. Restrictive trade measures have outstripped liberalising measures three to one this year and increased by almost five times since 2009, as policymakers try to circumvent the WTO. Meanwhile, the deleveraging of banking balance sheets over recent years has hit global lending, as banks retreat from peripheral to core domestic activities, cutting vital credit flows through key arteries.

All of this preceded the populist deluge of 2016 and, indeed, contributed as policymakers myopically prioritised stability over social cohesion, ignoring the lessons of the past.

But globally, politicians are now fast realigning to shifting public moods. A year ago, to imagine a world where the major western leaders included Trump, the Brexit brigade and Marine Le Pen was the province of satire. Today, we are two-thirds there. Their ascendancy has shifted the political debate towards nativism in a hauntingly familiar nationalist narrative, as others follow suit.

Our new politics are not leftwing or rightwing, merely whether you are in this world or out of it. Even defenders of globalisation are falling into the same trap. By demonising those that voted against and not providing alternative options, they cling tighter to those that confirm and affirm their beliefs. That is still nativism of a different sort and still the politics of division, not unity.

This is Deglobalisation 2.0.

Monetary policies such as quantitative easing and its newborn sibling, fiscal easing, cannot change this dynamic. Absent structural change, their cumulative corrosive impact on savings and fillip to global debt ensure a limited runway and only inflame the rhetoric of disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, divorces are turning ugly as emotions override reason, viz the talk of Brexit fees and anti-dumping levies, the metaphorical Kristallnacht of populist victors like May and Trump as they struggle for coherence, and emerging divisions between central banks and politicians, to name but a few.

Democracy is fast turning to kakistocracy – government by the least qualified leaders. Globalisation is transmuting to nationalism. The effects are well documented in history – autarky, economic naivety, protectionism and a rush to grab what remains of the pie, only to trample it underfoot.

'Me first' always ends in 'me last'. The world is still getting smaller, but just in our minds and horizons now, and thoughtless we risk becoming all the poorer for it.