Bob Swarup and David Worsfold

Download this piece as a PDF by clicking the link below

Of No Fixed Abode - The evolution of fixed income in today's world

The Insurance Investment Exchange events in March and May 2015 tackled a key dilemma for insurance companies: in today’s environment of challenged yields and regulatory change, where does the fixed income portfolio evolve to next? This thought leadership paper from summer 2015 echoes the ensuing debate, mixed in with our own analysis of macro and industry dynamics.

Abenomics. Draghinomics. Investor shock and monetary awe. Negative yields. Lower for longer. The new normal. Bond bubbles? And tail risk trouble?

This is the stuff insurance nightmares are made of. This is also the evolving macroeconomic reality that insurance companies inhabit, underscoring the need to think outside the box and innovate new approaches.

QE and Quo Vadis

We live in a world of unconventional monetary policy, where economies cluster at the zero interest rate bound and the ‘Big Four’ central banks (the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, the Bank of England and the Bank of Japan) have a combined balance sheet of $10 trillion after years of stimulus. Debt burdens are high. Wage growth is anaemic at best. The concomitant social tensions are evident. And geopolitical tensions are making an unwelcome return to the global stage after the extended entente cordiale of the last 25 years.

The situation gets more complicated. With the exception of the US, the rest are struggling to maintain the facade of growth. Japan’s bold ‘Abenomics’ experiment has failed to deliver so far, and Europe is battling the demons of Greece once again. China’s growth is slowing rapidly as its debt burden becomes destabilising, while growth in the other BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) is turning out to be mostly half-baked. Even where quantitative easing has had some success (chiefly, the US and UK), real wages have been stagnant.

These are not the foundations that policymakers wish for when planning for recovery. Inflation is conspicuously absent, and with it, any realistic prospect of deleveraging in real terms. Even in the US, where growth has been sustained in recent quarters, the Federal Reserve has made it clear it is focused on unemployment reduction and wage growth as key determinants of genuine success. So far, there is very little evidence that these policies are delivering sustained results.

Throw falling oil prices into this disinflationary environment and you ratchet up the stress factor for policymakers. Already, the rapid fall in oil prices has caused inflation to significantly undershoot expectations. Europe tipped into outright deflation in December while the UK CPI fell to 0% in February – the lowest since records began. Meanwhile, the wider risks to growth mount. Against the stimulus of lower oil prices, the IMF cited lower investment, market volatility, stagnation in Europe and Japan, and geopolitical events as risks that forced them to revise global growth lower by 0.3 per cent.

Alongside – much as ‘good’ deflation from China in recent decades stretched pay-packets further, even as they shrank in real terms – falling oil prices enhance disposable income and dampen the conventional dynamics that might push wages higher. Annual wage growth is likely to continue to disappoint, heaping further pressure on policymakers, although the latest UK data has given the first glimmer of hope on this front.

The natural reaction for policymakers is to postpone any tightening and reach for further monetary stimulus in an effort to stoke inflation and demand. The amount is simply proportional to their fear of deflation.

Quantitative easing – once unconventional – is now conventional warfare for those at the zero interest rate bound. Japan has renewed its vows of marriage to Abenomics. The ECB may have come late to the QE party but Mario Draghi has unveiled an ambitious €1.1 trillion programme of bond buying that original thinkers have christened Draghinomics. Even the US is under more pressure now to leave interest rates lower for longer and maintain an accommodative stance, thanks to the strengthening US dollar. Under these circumstances alone, the balance sheet of the Big Four will grow by some 25 per cent to nearly $13 trillion by the end of 2017. This is a huge amount of monetary stimulus on top of the $500bn of ‘fiscal’ stimulus already provided by falling oil prices. The real danger, perhaps even likelihood, is one of hyper-stimulus.

The quantum of stimulus already to date and its distortion of the yield curve have proved powerful steroids to financial markets. Add in more, and you suppress yields even more. As an example, the pool of European bonds with negative yields has increased a hundred-fold from $20bn to over $2 trillion In just a year. This reinforces both the vicious crush for yield that has driven investors (particularly those with liabilities) into every asset class that promises a ghost of a return, and the moral hazard of the policymaker put option.

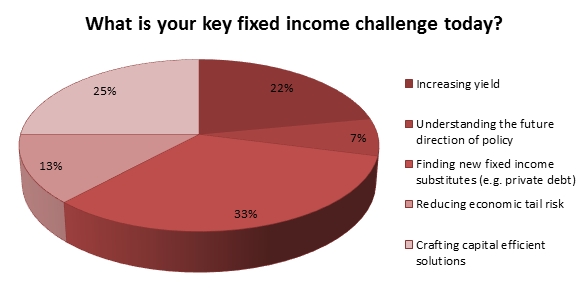

The Hunt for Yield

The previously uncharted economic background is a toxic dynamic for insurers. The need to match assets and liabilities, coupled with the advantages bestowed by the vagaries of regulatory capital, have made the industry firm adherents to the cult of fixed income over the last few decades. But today, what was once a comforting contractual bulwark against uncertainty has become a crushing burden. Low yields exacerbate and arguably exaggerate liabilities. They also make it harder for assets to generate the cashflows needed to meet liabilities as well as generate shareholder returns. A survey at the March event found that 4 out of 5 insurers saw increasing yields, finding new fixed income substitutes and minimising regulatory drag as their key challenges in fixed income.

Figure 1: The key fixed income challenges for insurers today (Source: IIE survey, March 2015)

Value and quality have demerged in today’s world. The result is a continual pressure to find higher yields and new sources of cashflow as the old staples prove inadequate to the challenge. However, as money has poured into new areas, the spreads have often tightened, thanks to the limited capacity of these nascent areas, increasing risks. At the same time, new risks are also being taken on that are less understood and easily quantified.

Yet, a perverse dichotomy has emerged, as risk aversion has not shrunk but grown in recent years. As humans, we are all prey to the asymmetry of losses and gains. In other words, a loss of say £100 wounds us far more deeply than the pleasure derived from winning the same amount. The painful memories of 2008 are still fresh in many minds, and there is strong cultural opposition – not always misplaced – within insurance companies to newer asset classes.

Regulation has further complicated the picture. The prescriptive nature of incoming rules, such as Solvency II, create a strict environment of demands with implications for regulatory capital requirements across the industry. It is hard for a person to serve two masters, and insurers are waking up to this as they seek to tap new sources of returns whilst also maintaining returns of capital and profitability. Limits on asset eligibility (e.g. as in the matching adjustment), look-through to underlying exposures, the importance of data quality, the focus on quantification and the rose of risk management up the totem pole – these are all challenges for insurers looking to stray off the well-trodden paths of public fixed income and their like.

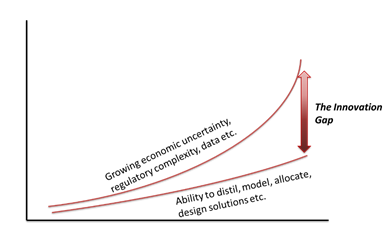

There is a widening gap today between the complexity and increasing demands of the outside world, and the ability of insurers to keep apace, which will only worsen in the absence of change. The growing need is for a holistic rethink of insurance approaches to asset allocation, asset-liability management and regulatory capital. There is a need, in short, for that most bastardised of words – innovation.

Figure 2: The growing innovation gap for insurers (Source: Camdor Global)

What does innovation look like?

If innovation is the key to unlocking higher fixed income returns, what does that innovation look like? As noted earlier, in the current environment, it means an all-encompassing rethink of investment strategy, approaches to risk and capital management, and the internal culture across an organisation. This isn’t a challenge for the timid.

Figure 3: The spectrum of innovation for insurance companies (Source: Camdor Global).

As spreads have tightened in recent years, insurers have moved from domestic markets to international markets, first developed and then emerging. They have moved further down the credit curve from investment grade fixed income towards high yield bonds. Structured credit in its different flavours (ABS and MBS) has become a mainstream allocation. But according to some insurers, the trouble is that these usual suspects – so often trotted out as the first alternatives for the fixed income portfolio – are now looking tired and squeezed of value. Given the massive compression in yields post 2008, finding new value here will be a challenge, though some are battling to find as yet under-exploited pockets. There are also new macro uncertainties to consider given the proliferation of oil and gas companies in the high yield space, and the rapid growth in dollar-denominated emerging market debt. Both face increased risks given the fall in commodity prices and the strong US dollar.

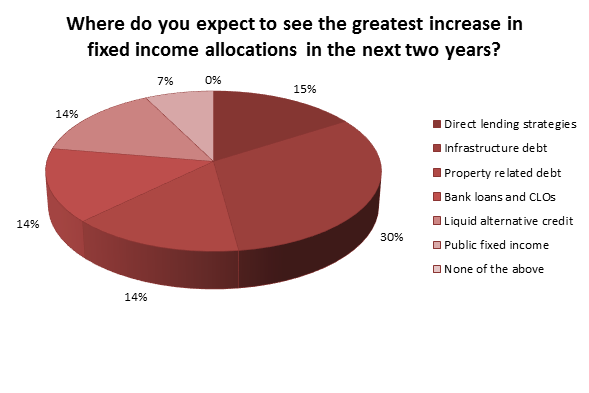

More recently, interest has grown in alternative credit – a wide heterogeneous field encompassing direct lending, infrastructure debt, commercial real estate lending, distressed debt, mezzanine, insurance-linked securities, trade finance, leverage loans and liquid hedged credit strategies to name but a few. 93% of insurers see this wide space as the recipient of their fixed income flows in the coming two years.

Figure 4: Where insurers’ fixed income allocations are expected to flow in the next two years (Source: IIE survey, March 2015)

But as insurers take their first steps, the need to think carefully about asset allocation vis-à-vis their own requirements and understand the new dynamics of these asset classes is becoming clear. Equally, they require a wholly different due diligence approach, both in choosing managers as well as on the underlying assets.

For example, property debt such as commercial real estate lending has seen a rapid compression of yields when it comes to prime areas and senior debt, as the flows of money and competition from other institutional investors, such as pension funds, have overwhelmed limited capacity. Areas such as infrastructure debt and social housing are popular from an allocation perspective, but spreads are tight in segments of the market and origination is a growing concern. There are also dislocations between supply and demand, with insurers unwilling to take developmental risk despite the bulk of deal flow emerging in new infrastructure. Bridging that gap requires both deal bespoking and structuring. And there are large segments of the market for which these are wholly inappropriate. Typically, infrastructure assets are illiquid and it is unclear whether there will be a ready secondary market if investors need to sell – a particular concern for property and casualty insurers who could be forced to realise assets at short notice if faced with large catastrophe claims. Where pockets of value are emerging, they are often in complex areas such as direct lending, mezzanine financing, esoteric credit, bespoke hedging strategies, and so on.

Two key and inter-related themes emerging in our discussions with the industry are the need to think carefully about portfolio construction and the need to penetrate this greater complexity. Alternatives by themselves are not a de facto better choice. They are a set of new tools that properly used could provide significant benefits to insurance portfolios and returns on capital. That requires a carefully thought through and judged approach as to their place within the portfolio, an understanding of their proclivities and dynamics, and a careful management of the new risks acquired. Otherwise, a knee-jerk and scattergun approach is likely only to prove a hindrance, converting the greener grass on other side of the fence into a minefield.

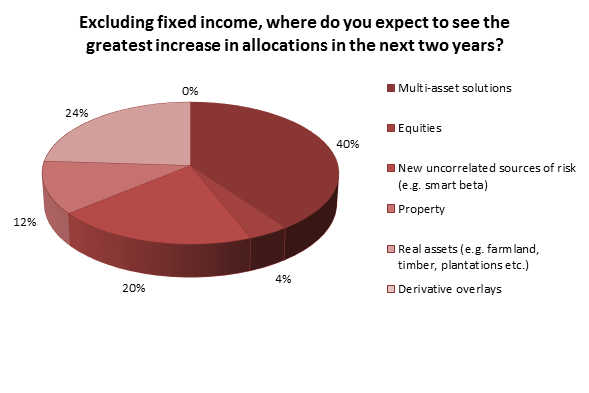

Different strategies will also develop in the life and P&C markets, given their differing liability profiles, and especially as Solvency II is bedded down. With eyes now wandering towards areas outside fixed income and considering a wider range of allocations from multi-asset solutions to smart beta to real assets, it is clear that a) insurers are thinking harder about how to construct portfolios and manage their risks; and b) that these challenges are not going to diminish anytime soon.

Figure 5: Where insurers expect to allocate over the next two years outside of fixed income (Source: IIE survey, March 2015)

ACE-ing it – the Importance of Appetite, Culture and Expertise

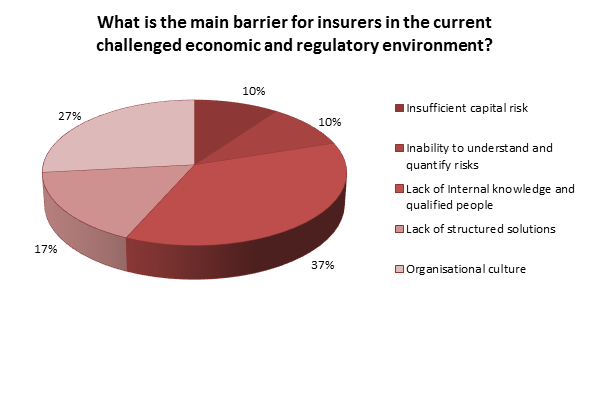

Not surprisingly, the most common fears echoed about a successful resolution to the above issues are whether insurers have the organisational culture to embrace change; whether investment and risk committees really have the appetite for embracing the new (or greater, depending on your perspective) risks these new asset classes represent; whether firms have the actual expertise to assess and monitor these new strategies; and whether these can be structured to fit within the strictures of regulation.

Figure 6: The main barriers for insurers today in evolving their fixed income allocations (Source: IIE survey, March 2015)

These are all valid concerns and point to the need for innovation beyond just evolving the investment strategy. With the value likely to be found in highly specialised, sometimes esoteric, assets, many of which require detailed fundamental credit analysis or have to be directly owned to get significant enough payback – solar panels, wind farms, social housing schemes, infrastructure projects and their like – expertise will be at a premium. The fear of many insurers and managers is that this will be the major constraining factor, alongside organisational caution at the senior level.

The size of institution will also be a key factor in the type of assets they can manage. Some fear that too few institutions are large enough to understand and embrace the diversity of assets required to make up a quality fixed income portfolio in 2015. Only the very largest could contemplate direct investment in something like the Paddington Central development, a high risk scheme split into six phases over 10 years, or the recent acquisition of stakes in Associated British Ports and Eurostar by Canadian-UK consortiums. Smaller institutions will instead be attracted to the range of open and closed funds as well as mandate offerings that are emerging to give them access to these asset classes. But here, their emphasis will need to shift to assessing the manager’s own abilities to originate, analyse and monitor assets.

Internal teams are also small and often made of generalists rather than specialists. They have few means of keeping apprised on the changing dynamics across these diverse asset classes, and comparing them both to each other as well as to traditional staples to reach the best decisions.

Traditionally conservative investment and risk committees will have to be coaxed gently into this new world, although many felt this could be a serious blockage. Overcoming that will require a well balanced approach to governance with good quality data and metrics put alongside intelligent qualitative and quantitative analysis. The challenge will be to develop a risk culture appropriate to the size and position of the business, and then to put the appropriate risk models and policies in place.

While the search for quality and value goes on, other pressing challenges cannot be ignored. From a regulatory perspective, capital is not the binding constraint surprisingly. Many feel they have sufficient capital to deploy intelligently. Equally, modelling capital charges is not the issue, given the huge investment that has been made across the industry in developing internal models and upgrading the risk architecture.

Rather, the key problem is one of ensuring that an attractive yield or risk premium translates also into a healthy return on capital deployed. Insurers are businesses first and foremost, and so return on capital as well as profitability are paramount. The leverage inherent in the business model coupled with the sympathetic regulatory treatment of traditional fixed income means that even at these minute spreads, there is a return on capital to be extracted.

This is a barrier to allocation for many of the new emerging asset classes, as they are not in the first instance often in the right form or structure for the insurance balance sheet. The detailed implementation of Solvency II remains a significant concern for many insurers and is likely to remain so for a while yet.

Life insurers, for example, are hostage to the matching adjustment, which mandates fixed and ideally investment grade rated cashflows to maximise the benefit. Even where this may not be a constraint, the ability to structure cashflows and manage credit risks will make significant differences to both the embedded risk as well as the capital deployed. That requires more alternatives expertise, particularly on the structuring side, which currently is in short supply for both managers and insurers.

Looking to the Future

These have all been recurring themes at the IIE seminars to date. The focus on education and the need to create an appropriate organisational culture through dialogue and the sharing of ideas remains as strong as ever. Expertise is also growing, with credible new providers and solutions coming onto the market focused on alternatives and efficient structuring. What the final landscape looks like is yet to be determined but the signs of movement and growing engagement are encouraging.

We also should not forget the bigger picture. Given the quantum of assets in fixed income, traditional fixed income will still be the dominant portion of many portfolios even after all these changes. Understanding how to manage it, mitigate its risks, and evolve it alongside a changing wider framework is also critical. At some point, the pendulum will swing again. We ignore it at our peril.

Coupled with the nature of liabilities, this also means that insurers will continue to be highly exposed to the uncertainties of policymakers and their impact on yield, inflation and credit curves. The changes to annuities and the fresh challenges created, as well as the debate surrounding the timing of rate rises, are but two recent examples.

At the same time, some of the new risks acquired are political, geopolitical, regulatory and so on, depending on the asset class (as some in infrastructure have already learnt). Macro matters like never before.

The journey ahead is uncertain but the light is also getting clearer. And if we can talk, share and learn from each other along the way, it will seem all the shorter and more rewarding.

Bob Swarup is the co-founder of the Insurance Investment Exchange and Principal at Camdor Global, a strategic advisory firm focused on investment strategy and risk management.

David Worsfold is an adviser to the Insurance Investment Exchange and an award-winning journalist. He has written about the insurance sector and wider financial services for 30 years for a wide range of national newspapers and specialist business titles.