David Worsfold

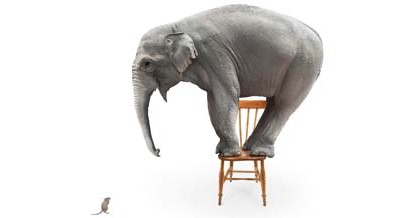

Whenever the threat of a Brexit vote in the June referendum is discussed in City boardrooms, you can almost count the elephants lining up around the walls. Those in favour of staying in – the overwhelming majority – talk of chaos and trade barriers but rarely of specifics. Those advocating the UK leaving implausibly play down the negatives.

Ask the senior management of UK-owned and UK-based insurers whether they have factored the possibility of the UK voting to leave the European Union into their 2016 scenarios, and most are quick to reassure you that they have done so. Press them on what that scenario looks like and most will start by talking about short term uncertainty but then quickly make reassuring noises about a minimal medium to long term impact. Never do they spell out publicly their darkest fears about the threat to their markets, their assets or their longer term strategies.

Brexit was perhaps a distant threat for a long time, maybe even receding in the eyes of many, with the Prime Minister’s strong advocacy for staying in in the wake of the recent EU summit. Then, one by one, Conservative political heavyweights capable of adding both intellectual credibility and popular appeal to the Leave campaign came off the fence, most recently and not least the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson.

Dismiss Johnson’s stance as one driven by naked ambition all you like, but it does have substance behind it in the form of his chief economic adviser, Gerard Lyons, who spoke to a group of European journalists and commentators, including the Insurance Investment Exchange, last week.

Lyons is no blinkered isolationist and also is not frightened to point out a few of the above mentioned elephants lurking just over his shoulder. In 2014, he wrote The Europe Report: a Win-Win Situation, arguing that the best future for Britain lay in continued membership in a much-reformed EU. Before joining the City hall team in 2013, he held senior roles at leading banks in the City, including Standard Chartered and Chase Manhattan. Today, he sits on the advisory board of the Open Europe think tank.

Gerard talks a lot about the need to reclaim national sovereignty, especially in the context of controlling migration and protecting the UK from the Eurozone. But he is also honest about the challenges the City and the financial services sector will face in the event of a Brexit vote.

“If we vote to leave, there will be a short term economic shock which will impact growth and jobs as businesses put investment plans on hold. The consequences of that will play out over time, but as they do, we will start to benefit from the greater freedom the UK will have”.

He acknowledges that the exit process could be brutal, especially if Article 50 of the EU Treaty is enacted. This imposes a rigid two year timetable on exit: “Article 50 is untested but if they follow it, the UK will be completely excluded from the first stage of the process. The remaining members will meet and agree the terms to be put to us. We cannot exclude the possibility that the EU might act irrationally in the wake of a Brexit vote”.

Notwithstanding, even acting rationally might be bad enough. Lyons admits that it would be almost certain that the hard-won victory over Euro-clearing last year would be overturned, meaning British companies managing financial trades in Euros would have to relocate to the Eurozone. There would also be strong downward pressure on the Pound, though not something that unduly concerned him.

In the wake of a Brexit vote, the policy priorities according to Lyons would be to rebuild the competencies we have handed to Brussels over the last 40 years, key amongst them, the ability to handle major trade deal negotiations: “The ability to negotiate the best deals for the UK, freed from the need to compromise with 27 other countries, is one of the most important benefits of leaving. However, we know it is a competency we have lost from Whitehall”.

This is a refreshing acknowledgment of the scale of the challenge the UK would face in initiating a series of bilateral trade negotiations, not least with an EU that might be feel it needs to be clear on the huge downsides of anyone storming out of the room, only to poke their head back round the door and ask for a nice chat about favourable trade deals.

There was also none of the naïveté of some Brexit campaigners about ditching unwanted volumes of EU regulations: “Many of those that our financial institutions are subject to, are now set globally by the FSB [Financial Stability Board] and the G20. The EU is not where the important discussions take place anymore”.

Lyons recognises that the referendum on 23 June is not going to be won or lost on purely economic and regulatory arguments. The issue he believes that will motivate most people to vote to leave the EU is migration. And the bigger the Brexit vote – victory if that is what we are talking about – the tougher will be the UK government’s attack on migration. This could have a serious impact in several areas, not least construction and infrastructure, where the shortage of UK labour has made the recruitment of thousands of workers from Eastern Europe essential. Investors and investment managers might want to contemplate the impact this could have on their portfolios.

The one elephant in the room that Lyons – and others supporting Brexit – seem to feel most uncomfortable about acknowledging is one that has some of the most serious implications for the financial services sector – the future of the United Kingdom.

The prospect of a second Scottish independence referendum if the UK votes to leave was not something Lyons was keen to talk about, but the likelihood has to be high and the chances of Scotland leaving the UK and seeking EU membership in its own right is a strong possibility.

At the time of the Scottish referendum, it was assumed that there would be an exodus of Scottish financial institutions south of the border. Many had optioned thousands of square metres of office space in the City of London as a contingency.

It would be a rather different scenario with England, Wales and Northern Ireland out of the EU but Scotland potentially in.

Perhaps this time, the institutional migration might be the other way.